Pre-performance anxiety (PPA) has been identified as a mental factor that can impact athletes’ performance in sport (1, 2, 3), with 30-60% of athletes who voluntarily participate in sport reporting feelings of anxiety in relation to their performance (4, 5). Pre-performance anxiety is a negative emotional state that occurs before an athlete partakes in a sports event (i.e., game, practice) or task within sport (i.e., penalty shot, free kick). Stress and anxiety are common in sport (6), as athletes must deal with standards for success, pressure from coaches, family, or media, and exposure to criticism (1). Because of the stress factors many athletes are exposed to, they are at a high risk of experiencing performance anxiety, which can lead to problems with motivation, performance, and confidence (7, 8, 9, 10). However, there are strategies that coaches can use to help athletes manage their pre-performance anxiety symptoms, as they are designed to help athletes cope, manage symptoms of pre-performance anxiety, and support them if they experience it. Pre-performance anxiety can be interpreted differently by athletes depending on their experiences. For example, an athlete may feel anxious about their performance, but may also feel confident and positive about their abilities, which will help them to interpret their pre-performance anxiety as getting ready to perform. However, if an athlete lacks confidence or feels they lack ability, they may interpret their pre-performance anxiety as more harmful. Developing a pre-performance or pre-event plan which includes implementing strategies to help athletes manage pre-performance anxiety symptoms can be a more effective approach than trying to help an athlete after they experience pre-performance anxiety. Because pre-performance anxiety can impact an athlete both within sport and outside of it, offering skills and strategies to help manage their experience is very important.

Pre-performance anxiety is different from clinical anxiety. Pre-performance anxiety is related to a specific situation or environment (e.g., game, gym, penalty shot), only occurs within a certain situation or environment, and only lasts for the duration of the situation or time within the environment. Clinical anxiety is not triggered by a specific situation or environment. It can occur at seemingly random times, continue for long periods of time, produce extreme reactions, and be overwhelming for the individual. Recognizing these differences is important, as you may have to provide different kinds support to an athlete experiencing clinical anxiety. The information provided on this website is designed to address pre-performance anxiety and should not be used to manage clinical anxiety.

- What can pre-performance anxiety impact?

- Sport performance (1, 2, 3, 7, 8)

- Motivation (7, 10)

- Working memory (11)

- Working Memory is important for making decisions and maintaining attention and concentration (12)

- Sense of control (11, 13)

- Having a sense of control can help athletes manage their thoughts and feelings and feel capable of performing well.

- Confidence (11, 9, 14)

- Well-being (7, 15)

- What causes pre-performance anxiety?

- When an individual perceives the environment or something in their environment to be unique, threatening, or potentially harmful to their performance (11, 16)

- Unclear role on a team (17)

- Having a clear role within a team helps an athlete focus on their individual tasks and goals. If an athlete’s role is unclear, they may feel anxious about what is expected of them and these feelings may impact their performance.

- Feeling unprepared

- High-stakes games

- Last-minute changes (i.e., location, time, lineup)

- Either internal and external pressures of a sport (18)

- For example, internal pressures may result from:

- Pressure from the athlete themselves to perform well

- Lack of self-confidence or commitment

- Feelings of uncertainty or letting down oneself or others

- For example, external pressures may result from:

- Pressure from coaches, teammates, scouts, parents, or friends to do well

- Spectators

- The level of competition

- The consequences of success or failure

- The location

- Athletes are more likely to experience pre-performance anxiety at away competitions

- For example, internal pressures may result from:

Symptoms

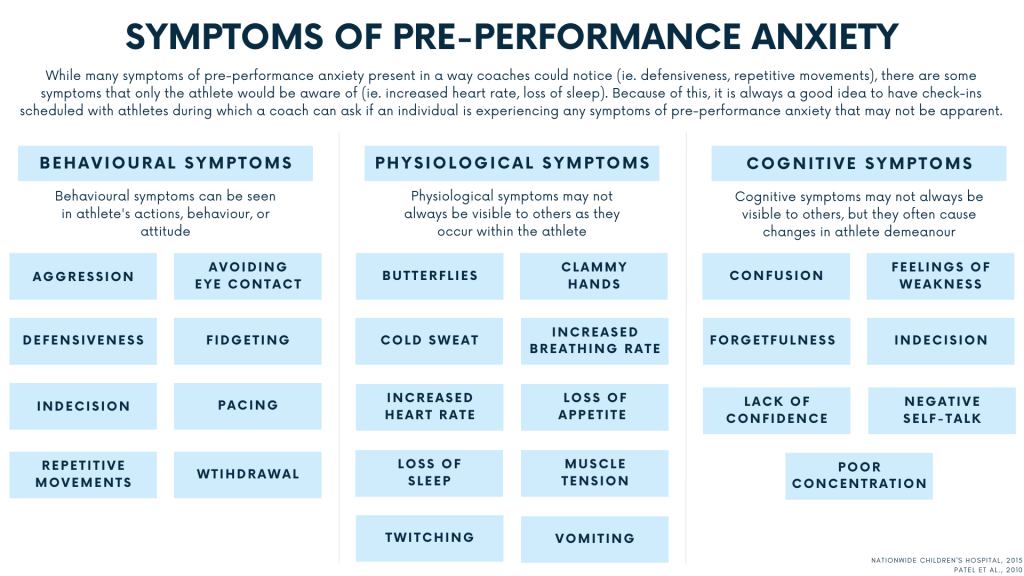

What are the symptoms of pre-performance anxiety? What should coaches be looking for?

While many symptoms of pre-performance anxiety show up in a way that are noticeable for coaches (i.e., defensiveness, repetitive movements), there are some symptoms that only the athlete would be aware of (i.e., increased heart rate, loss of sleep). Because of this, it is always a good idea to have check-ins scheduled with athletes so you can ask how the athlete is doing and ask if they are experiencing any symptoms of pre-performance anxiety that may not be apparent. Check out the infographic below that outlines the kinds of symptoms athletes may experience.

Can pre-performance anxiety be good?

Pre-performance anxiety can have both positive and negative effects on athletes (19, 20, 21, 22). How the anxiety affects the  athlete depends on how they interpret the symptoms they experience, as interpretations can be either facilitative (helpful) or debilitative (hurtful) to performance. Athletes that have a more facilitative perception of their anxiety symptoms view stressful situations as a challenge, are better able to use coping strategies, feel more confident, and often perform better. Athletes that have a more debilitative perception of their anxiety symptoms view stressful situations as threatening to performance, and often struggle to cope with their symptoms effectively. A good way to understand how the athletes you work with perceive their anxiety symptoms is by asking them.

athlete depends on how they interpret the symptoms they experience, as interpretations can be either facilitative (helpful) or debilitative (hurtful) to performance. Athletes that have a more facilitative perception of their anxiety symptoms view stressful situations as a challenge, are better able to use coping strategies, feel more confident, and often perform better. Athletes that have a more debilitative perception of their anxiety symptoms view stressful situations as threatening to performance, and often struggle to cope with their symptoms effectively. A good way to understand how the athletes you work with perceive their anxiety symptoms is by asking them.

Help Athletes Recognize and Reflect on their Pre-Performance Anxiety

To learn how to help athletes recognize and interpret their symptoms accurately, check out the Symptom Interpretation Resource.

To help athletes recognize and reflect on their symptoms of pre-performance anxiety, give them the Pre-Performance Anxiety Worksheet for Athletes¸ worksheet. This worksheet asks athletes about the symptoms of pre-performance anxiety they experience, how they perceive those symptoms, how they control or manage their symptoms, how they perform when experiencing symptoms, and how their symptoms make them feel. The worksheet will provide you with a better understanding of how each of your athletes experiences pre-performance anxiety and whether they interpret their symptoms in a helpful or hurtful way.

Depending on how your athlete(s) say they are affected by their symptoms, you can use the Pre-Performance Anxiety Worksheet Guide for Coaches to determine the appropriate resources and strategies to help them deal with pre-performance anxiety. Use this worksheet early in the season to start the discussion about how athletes feel before events, then you can use the strategies provided to help those who experience pre-performance anxiety to help them manage their symptoms closers to the event. We recommend utilizing strategies within a week of the event.

To learn how to help athletes manage their physical symptoms of pre-performance anxiety, check out the Strategies for Managing Physical Symptoms handout.

To help athletes learn how to cope with their physical symptoms of pre-performance anxiety, check out the Acknowledge and Address Worksheet

Addressing Athletes Respectfully

- How to address athletes appropriately and respectfully?

- The most important thing to remember when addressing pre-performance anxiety in athletes is that their experiences are very real. Pre-performance anxiety can be harmful to performance, and impact both an individual’s athletic identity and personal life. Coaches should acknowledge that what their athlete is feeling is very real and that performance anxiety can be managed with the right strategies, some patience, and of course, support from those around them. Check out our Coach Self-Evaluation Worksheet to reflect on your current strategies for interacting with athletes, and to get some helpful tips for doing so respectfully.

- When to call in reinforcements?

- If you notice an athlete is experiencing severe pre-performance anxiety and it’s effecting multiple aspects of their life and personality, it may be time to call in some reinforcements. There are many options that you as a coach can provide to an athlete who is struggling, and providing these resources is just as supportive as trying to help them yourself.

- We have provided some extra Resources you or your athlete(s) can reach out to. You can share the whole page with the athlete, or just offer the resources that may be appropriate.

Pre-Performance Anxiety Management Strategies

Below we provide three categories of strategies and skills that you can use to help your athlete(s) manage pre-performance anxiety. Each strategy has a summary and some information for you to familiarize yourself with, different ways to implement the strategy, and worksheets that can be passed out to athletes to help guide them and provide extra practice.

Self-Confidence Support Strategies

Success in sport boosts self-confidence (23, 24, 25), making it an important part of an athlete’s experience. Self-confidence is an athlete’s belief that they are capable of performing well, meeting challenges, and succeeding within their athletic environment. One of the symptoms of pre-performance anxiety is a lack of self-confidence (9), which often occurs when an athlete feels they aren’t capable of handling a challenge or feel they can’t succeed in the conditions they are performing in (26). A low sense of self-confidence can cause an athlete to feel less in control (27, 28), have trouble coping with their worries, and struggle to make decisions (26, 29), all of which contribute to feelings of pre-performance anxiety. Supporting athletes by helping them boost their confidence can be an effective way to reduce some of the negative effects of pre-performance anxiety and can help them to interpret things in their sporting environment more positively (e.g., seeing something as a challenge rather than an obstacle or stressor) (21, 26, 27).

Now that you’re familiar with self-confidence in sport and how it relates to pre-performance anxiety, you can try out some of the strategies that have been found to boost athletes’ confidence. Below, we have provided three ways that you can help support your athlete(s) by fostering their confidence. We recommend starting with SMART goals, as it is the easiest strategy to implement and will start a conversation about what your athlete(s) hope to accomplish. We recommend giving these strategies to athletes to work on outside of game, practice, and training time. You can explain the strategy or run through it during a practice to make sure they have the right idea, but then ask them to practice the strategy on their own. This allows them to focus on themselves and reduce the amount of distractions or interruptions using found in a game/practice/training environment.

Setting Goals

When working with your athlete(s), it is important to help them goals. Long-term goals may not provide the same support as short-term goals – by creating goals, athletes can feel as though they have the ability to meet the goals they have set. When goals are achieved, athletes feel like they’re getting more positive feedback, which helps to give them confidence in their abilities (30), and can help in the management of pre-performance anxiety. Review the Goal Setting page for more information, worksheets, and helpful infographics!

Imagery

Mental imagery, also called visualization, mental rehearsal, and mental practice is viewed by coaches and researchers as one of the most important psychological skills (31). It is considered a multidimensional process that refers to “an experience that mimics a real experience” (p.389) (32). Researchers have reported that the more senses you include, the more realistic it is compared to the actual experience, which will result in greater benefits (33). Imagery can be used to help athletes develop or maintain a healthy sense of confidence (34), and the skill can be utilized in both team and individual settings (35). Motivational general-mastery imagery is the most appropriate kind of imagery when targeting self-confidence (36). Motivational general-mastery imagery consists of thinking of images related to confidence, control, and mental toughness. Picturing yourself scoring the game-winning goal, succeeding at a skill, or outplaying your opponent are all examples of confidence-building motivational general-mastery imagery. Use the Mental Imagery Worksheets below to help athletes practice the skill of mental imagery. When developing the imagery scene, focus on picturing a scene in which the athlete overcomes a challenge, successfully completes a task, or wins a challenging competition/game. Scenes that revolve around these situations provide the best opportunity for the development and maintenance of self-confidence, which can help athletes struggling with pre-performance anxiety manage their symptoms. For a team imagery activity, check out Mental Imagery Worksheet 1. For an individual imagery activity, check out Mental Imagery Worksheet 2.

Redefine Success

Success in sport is often defined by winning outcomes, and while winning is certainly an important aspect of sport, there are many small victories between championships. When an athlete feels they have control over their ability to achieve success, their confidence will increase. Controllable sources of confidence are the parts of performance that the athlete has the ability to personally change, such as their intensity in practice, skill mastery, and motivation. Uncontrollable sources of confidence are parts of performance that athletes may have no direct ability to change, such as the outcome of games or skill level of opponents. As much as coaches wish it was, winning is not a controllable factor of sport, so, to provide a controllable source of confidence, coaches must redefine their definition of success when working with athletes. How an athlete perceives their coaches’ standard for success can have a big impact on their self-confidence (37). For example, if an athlete has lost their last three games and feels their coach only cares about how many wins they have, their self-confidence can severely decline, and symptoms of pre-performance anxiety can arise as a result. Creating an environment in which success is defined by technique, improvement, and effort can help athletes maintain their sense of confidence, as these are things athletes have the ability to control. For example, placing emphasis on a skill an athlete showed improvement on, or providing a cue for how they can improve a skill may help athletes recognize that success can come from sources other than winning. Use the Redefining Success Worksheet for Coaches to see how you can change your definition of success and provide confidence support to athletes struggling with pre-performance anxiety. Once you have found some factors you would like to use to define success, you should share them with your athlete(s). Below are a few ways to share this information with athletes:

-

- Have a meeting to discuss your expectations and ideas of what success looks like. If you want to turn this into a group activity, check out the Success in Sport Activity Planner

- Provide athletes and/or parents with a copy of our Success in Sport Infographic for Athletes, which can be emailed, printed, or hung up in a team space

- Incorporate your definition of success into your team or program’s code of conduct

- Praise athletes when they achieve something that fits your definition of success (e.g., improving a skill, demonstrating resiliency)

Cognitive Restructuring Strategies

Anxiety is subjective (38), meaning that each athlete interprets feelings of anxiety in their own way. Sometimes anxious thoughts and feelings are positive, helping the athlete to feel prepared and ready to perform. But sometimes anxious thoughts and feelings are negative, holding an athlete back from performing at their best. Learning to recognize when an anxiety response is helpful versus harmful is an excellent skill that can help athletes label their feelings, alter negative perceptions, and better manage pre-performance anxiety. Cognitive restructuring is a strategy used by many individuals to take away the power of negative thoughts and feelings brought on by pre-performance anxiety. Cognitive restructuring asks athletes to reflect in order to recognize, challenge, and replace negative thought patterns with more positive thoughts and perceptions of anxiety (9, 39). Negative thoughts often lead to negative feelings and negative self-perceptions, which can result in increased anxiety and poor performance (39, 40).

Keep in mind that this strategy, while effective when implemented correctly, can take some time for athletes to master. Athletes must be willing to try this strategy, otherwise, they may find it frustrating due to the lack of immediate results. Learning to recognize thoughts that often fly through your head without question is a skill – one that takes time, practice, and trial and error. But once an athlete has mastered the skill, cognitive restructuring can help them to challenge their negative thoughts, alter their perceptions, and reduce the negative impacts of pre-performance anxiety. Check out the Cognitive Restructuring Infographic to get an idea of what cognitive restructuring looks like. The infographic outlines the steps involved in the strategy, provides examples at each step, and explains when cognitive restructuring can be used.

Cognitive Restructuring Worksheets

Below are some worksheets designed to guide athletes through the implementation of cognitive restructuring. We recommend giving these strategies to athletes to work on outside of game, practice, and training time. You can explain the strategy or run through it during a practice to make sure they have the right idea, but then ask them to practice the strategy on their own. This allows them to focus on themselves and reduce the amount of distractions or interruptions using found in a game/practice/training environment.

- The Cognitive Restructuring for Beginners Worksheet can be used to walk you through the steps of cognitive restructuring or given to athletes for them to complete. The worksheet outlines the ABCD technique often used when first starting to try out cognitive restructuring, asking athletes to identify a moment of adversity and then walking them through the steps of addressing and altering the negative thoughts and feelings they have in that situation.

- The Thought Adjustment Worksheet can be used to help you better understand the process of cognitive restructuring, or it can be given to athletes for them to complete. The worksheet asks athletes to identify a stressor in their athletic environment, reflect on the thoughts and emotions they have as a result of the stressor, and create alternative thoughts and feelings to help them manage any negative pre-performance anxiety symptoms that are brought on by the stressor.

- You can use the If-Then Worksheet to help athletes identify realistic outcomes of their actions. This worksheet can be given to athletes for them to complete. When an athlete experiences pre-performance anxiety, they may feel the quality of their performance will have severe negative outcomes (i.e., if I have a bad game today I will definitely be kicked off the team). It is important to help athletes address and alter these thoughts and feelings, because these negative assumptions can actually cause an athlete to feel more anxious. If an athlete seems to be particularly occupied with the consequences of a negative performance, this worksheet may be helpful!

- The Thought Adjustment Cues Worksheet can be used to walk you through the steps of cognitive restructuring or given to athletes for them to complete. Cues can be helpful tools when helping athletes manage their feelings of pre-performance anxiety. This worksheet asks athletes to identify when they feeling anxious and then pick something in that situation to act as a cue to start thinking more helpful, positive thoughts.

Performance Routines

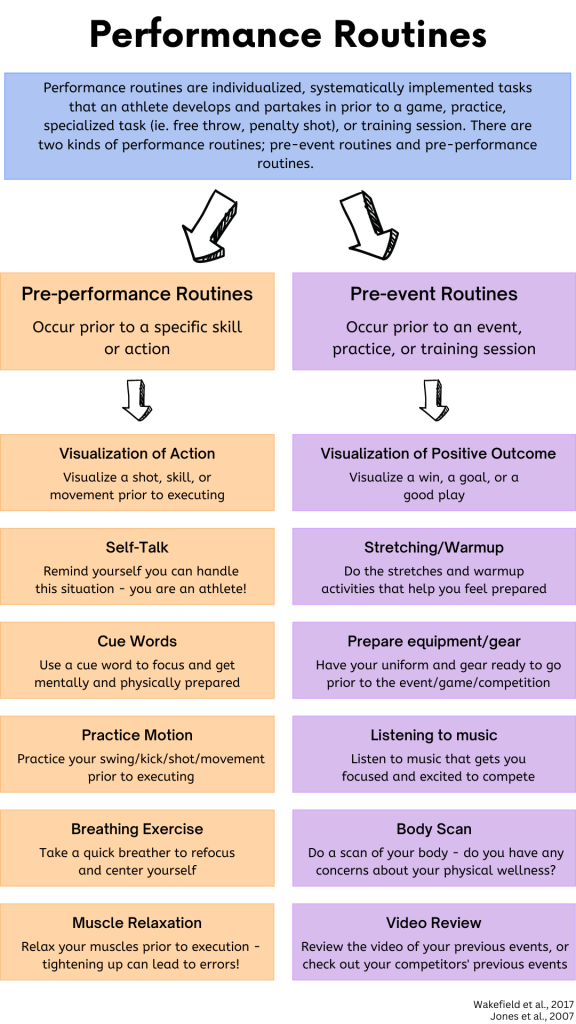

Performance routines are individualized, systematically implemented tasks that an athlete develops and partakes in prior to a game, practice, specialized task (i.e., free throw, penalty shot), or training session. There are two kinds of performance routines: pre-event routines and pre-performance routines. Pre-event routines occur prior to an event, game, practice, or training session (41). Pre-performance routines occur prior to a specific skill or action (42). For example, completing a series of stretches before a game would be considered a pre-event routine. Visualizing a successful free throw prior to executing it would be considered a pre-performance routine. Performance routines offer many potential benefits to athletes, as they may improve concentration and consistency, aid in anxiety management, lessen negative thoughts, and improve overall performance (43, 44), especially in beginner athletes (45, 46, 47, 48). If you want to work with your athlete(s) to designed a performance routine, check out Performance Routines Worksheet 1 and Performance Routines Worksheet 2.

Performance routines are used by athletes for many reasons, because they can help with anxiety management, concentration, consistency, and overall performance (5, 43, 49, 50, 51). When used to help manage pre-performance anxiety, these routines can help athletes reduce the negative impact of anxiety symptoms and help them to feel more prepared or in the zone prior to an event or performance. When developing a performance routine, it is important for the athlete to select elements of their routine that they have control over so they are able to adapt to any situation and complete their routine (42). This sense of control can help reduce the negative feelings associated with pre-performance anxiety by providing structure and attainable goals for the athlete to focus on prior to a performance. An athlete has control over an element of their routine when they are able to influence it themselves. Stretching in the same order, napping before the game, and visualizing a successful free throw would all be examples of controllable elements of a routine. Stretching in the example same place, napping at the exact same time, and having to make seven successful free throws would all be examples of non-controllable elements of a routine. Check out the Performance Routine Examples Infographic for some examples of tasks that can be incorporated into a performance routine.

Superstitions are often confused with performance routines. Superstitions are repetitive actions not relevant to technical performance that an athlete may feel the desire to act out prior to a sporting event (42). If an athlete is unable to complete their full routine of superstitious actions prior to performance, it can be extremely problematic, as their confidence in their ability, focus, and overall performance can be impacted (42). Examples of superstitions include always dressing in the same order prior to a game, having to eat the same meal at the same time every game day, and always having to sit in the same spot on the bus. These actions are not relevant to an athlete’s performance, as they do not prepare them physically or mentally to perform. Often if an athlete is unable to complete a superstitious behaviour, they feel as though their performance will be severely impacted or something bad will happen (e.g., injury, missed penalty shot). On the other hand, performance routines are designed to be relevant to the task and help to prepare the athlete physically or mentally to perform (42, 52). Engaging in a stretching routine before every game, visualizing the start of the race, and doing a breathing exercise before your performance are all examples elements of a performance routine. Check out the Routine vs. Superstition Infographic for more examples of what is considered a healthy routine versus what is considered a harmful superstition.

Performance Routine Worksheets

Below are some worksheets designed to guide athletes through the development and implementation of performance routines! We recommend giving these strategies to athletes to work on outside of game, practice, and training time. You can explain the strategy or run through it during a practice to make sure they have the right idea, but then ask them to practice the strategy on their own. This allows them to focus on themselves and reduce the amount of distractions or interruptions using found in a game/practice/training environment.

- The Performance Cues Strategy resource was designed for coaches to help provide insight into how cues can be incorporated into an athlete’s performance routine. It explains how cues can be helpful and provides some examples of cues that can be used in different situations. We recommend looking at this resource before sharing the strategy with your athlete(s), as it will help you get an idea of what an effective cue looks like and how to make sure there is purpose behind it. Once you have a good idea of this strategy, check out the worksheet below!

- The Performance Cues for Athletes Worksheet is designed to be given to athletes for them to complete. It explains why cues can be helpful when incorporated into pre-performance routines, and asks athletes to develop a few cues of their own, and reflect on how they may help – this helps athletes develop cues that are purposeful and task-relevant. The worksheet also provides some examples of cues used in certain situations and how they may help.

What’s Next?

There are many strategies you can use to help manage pre-performance anxiety. Now that you have had the opportunity to learn about them and try them out, it’s time to reflect on how it went. Did you find them helpful? Which one did you like the most? Which one didn’t work for you? Reflecting is a big part of mastering sport psychology skills – to figure out what works best for you, you must reflect on how each strategy made you feel and whether it did what it was meant to do. Use the Strategy Check-in Worksheet to reflect on your experience using these new strategies and figure out which ones you want to continue using in the future. This worksheet was designed to be used by both coaches and athletes. You can have your athletes complete the worksheet to reflect on the strategies they found helpful when they tried to manage their pre-performance anxiety, or you can complete it yourself and reflect on how the strategies fit within your coaching practice!

References

1. Sanchez, X., Boschker, M. S. J., & Llewellyn, D. J. (2010). Pre-performance psychological states and performance in an elite climbing competition. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 20(2), 356-363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00904.x

2. Craft, L. L., Magyar, T. M., Becker, B. J., & Feltz, D. L. (2003). The relationship between the competitive state anxiety inventory-2 and sport performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of sport & exercise psychology, 25(1), 44-65. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.25.1.44

3. Woodman, T. I. M., & Hardy, L. E. W. (2003). The relative impact of cognitive anxiety and self-confidence upon sport performance: a meta-analysis. Journal of sports sciences, 21(6), 443-457. https://doi.org/10.1080/0264041031000101809

4. Rowland, D. L., & van Lankveld, J. J. D. M. (2019). Anxiety and Performance in Sex, Sport, and Stage: Identifying Common Ground. Frontiers in psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01615

5. Mesagno, C., Marchant, D., & Morris, T. (2008). A Pre-Performance Routine to Alleviate Choking in “Choking-Susceptible” Athletes. The sport psychologist, 22(4), 439-457. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.22.4.439

6. Borkoles, E., Kaiseler, M., Evans, A., Ski, C. F., Thompson, D. R., & Polman, R. C. J. (2018). Type D personality, stress, coping and performance on a novel sport task. PloS one, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196692

7. O’Brien, K. T., & Kilrea, K. A. (2021). Unitive experience and athlete mental health: Exploring relationships to sport-related anxiety, motivation, and well-being. The Humanistic psychologist, 49(2), 314-337. https://doi.org/10.1037/hum0000173

8. Rice, S. M., Purcell, R., De Silva, S., Mawren, D., McGorry, P. D., & Parker, A. G. (2016). The Mental Health of Elite Athletes: A Narrative Systematic Review. Sports medicine (Auckland), 46(9), 1333-1353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0492-2

9. Patel, D. R. M. D., Omar, H. M. D., & Terry, M. B. S. (2010). Sport-related Performance Anxiety in Young Female Athletes. Journal of pediatric & adolescent gynecology, 23(6), 325-335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2010.04.004

10. Goodger, K., Gorely, T., Lavallee, D., & Harwood, C. (2007). Burnout in sport: A systematic review. The Sport psychologist, 21(2), 127-151. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.21.2.127

11. Brooks, A. W. (2014). Get excited: Reappraising pre-performance anxiety as excitement. Journal of Experiemental Psychology. General, 143(3), 1144-1158. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035325

12. Furley, P., & Wood, G. (2016). Working Memory, Attentional Control, and Expertise in Sports: A Review of Current Literature and Directions for Future Research. Journal of applied research in memory and cognition, 5(4), 415-425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2016.05.001

13. Raghunathan, R., & Pham, M. T. (1999). All Negative Moods Are Not Equal: Motivational Influences of Anxiety and Sadness on Decision Making. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 79(1), 56-77. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1999.2838

14. Han, S., Lerner, J. S., & Keltner, D. (2007). Feelings and consumer decision making: The appraisal-tendency framework. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 158–168. doi:10.1016/S1057-7408(07)70023-2

15. Silva, J. M., III. (1990). An analysis of the training stress syndrome in competitive athletics. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 2, 5–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10413209008406417

16. Brooks, A. W., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2011). Can Nervous Nelly negotiate? How anxiety causes negotiators to make low first offers, exit early, and earn less profit. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 115(1), 43-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.01.008

17. Beauchamp, M. R., Bray, S. R., Eys, M. A., & Carron, A. V., (2003). The effect of role ambiguity on competitive state anxiety. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 25, 77-92.

18. Gillham, E., & Gillham, A. D. (2014). Identifying athletes’ sources of competitive state anxiety. Journal of sport behavior, 37(1), 37-37. https://go.exlibris.link/WRxY9Kpx

19. Hatzigeorgiadis, A., & Chroni, S. (2007). Pre-Competition Anxiety and In-Competition Coping in Experienced Male Swimmers. International journal of sports science & coaching, 2(2), 181-189. https://doi.org/10.1260/174795407781394310

20. Jones, G., & Hanton, S. (2001). Pre-competitive feeling states and directional anxiety interpretations. Journal of sports sciences, 19(6), 385-395. https://doi.org/10.1080/026404101300149348

21. Jones, G. (1995). More than just a game: Research developments and issues in competitive anxiety in sport. The British Journal of Psychology, 86(4), 449-478. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1995.tb02565.x

22. Jones, G., Hanton, S., & Swain, A. (1994). Intensity and interpretation of anxiety symptoms in elite and non-elite sports performers. Personality and individual differences, 17(5), 657-663. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)90138-4

23. Cresswell, S., & Hodge, K. (2004). Coping Skills: Role of Trait Sport Confidence and Trait Anxiety. Perceptual and motor skills, 98(2), 433-438. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.98.2.433-438

24. Burton, D. (1988). Do anxious swimmers swim slower? Re-examining the elusive anxiety-performance relationship. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10, 45-61.

25. Hardy, L., Jones, J. G., & Gould, D. (1996) Understanding psychological preparation for sport: theoy and practice of elite performers. New York: Wiley.

26. Vealey, R. S. (2009). Confidence in sport. Sport Psychology, 1, 43-52.

27. Hanton, S., Mellalieu, S. D., & Hall, R. (2004). Self-confidence and anxiety interpretation: A qualitative investigation. Psychology of sport and exercise, 5(4), 477-495. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(03)00040-2

28. Jones, G., & Hanton, S. (1996). Interpretation of competitive anxiety symptoms and goal attainment expectations. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18, 144–157.

29. Eysenck, M. W. (1992). Anxiety: The cognitive perspective. London, England: Erlbaum.

30. Schunk, D. H. (1990). Goal Setting and Self-Efficacy During Self-Regulated Learning. Educational psychologist, 25(1), 71-86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2501_6

31. Rodgers, W. M., Hall, C. R., & Buckolz, E. (1991). The effect of an imagery training program on imagery ability, imagery use, and figure skating performance. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 3, 109-125.

32. White, A., & Hardy, L. (1998). An in-depth analysis of the use of imagery by high level slalom canoeists and artistic gymnasts. The Sports Psychologist, 5, 15-24.

33. Munroe-Chandler, K., & Hall, C. (2007). Sport Psychology Interventions. In P. R. E. Crocker (Ed), Sport Psychology: A Canadian Perspective (pp.184-213). Toronto, ON: Pearson

34. Yalcin, I., & Ramazanoglu, F. (2020). The effect of imagery use on the self-confidence: Turkish professional football players.Revista De Psicología Del Deporte, 29(2), 57-64.

35. Munroe-Chandler, K. J., & Hall, C. R. (2004). Enhancing the Collective Efficacy of a Soccer Team through Motivational General-Mastery Imagery. Imagination, cognition and personality, 24(1), 51-67. https://doi.org/10.2190/UM7Q-1V15-CJNM-LMP4

36. Hall, C. R., Munroe-Chandler, K. J., Cumming, J., Law, B., Ramsey, R., & Murphy, L. (2009). Imagery and observational learning use and their relationship to sport confidence. Journal of sports sciences, 27(4), 327-337. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410802549769

37. Machida, M., Marie Ward, R., & Vealey, R. S. (2012). Predictors of sources of self-confidence in collegiate athletes. International journal of sport and exercise psychology, 10(3), 172-185. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2012.672013

38. Kalisch, R., Wiech, K., Critchley, H. D., Seymour, B., O’Doherty, J. P., Oakley, D. A., Allen, P., & Dolan, R. J. (2005). Anxiety reduction through detachment: Subjective, physiological, and neural effects. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 17(6), 874-883. https://doi.org/10.1162/0898929054021184

39. Rowland, D. L., Moyle, G., & Cooper, S. E. (2021). Remediation Strategies for Performance Anxiety across Sex, Sport and Stage: Identifying Common Approaches and a Unified Cognitive Model. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(19), 10160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910160

40. Hill, D. M., Hanton, S., Matthews, N., & Fleming, S. (2010). A Qualitative Exploration of Choking in Elite Golf. Journal of clinical sport psychology, 4(3), 221-240. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.4.3.221

41. Jones, M. V., Bray, S. R., & Lavalee, D. (2007). All the world’s a stage: Impact of audience on sport performers. In S. Jowett & D. Lavallee (Eds.), Social Psychology in Sport (pp.103-114). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics

42. Wakefield, J. C., Shipherd, A. M., & Lee, M. A. (2017). Athlete Superstitions in Swimming: Beneficial or Detrimental? Strategies (Reston, Va.), 30(6), 10-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/08924562.2017.1369477

43. Cotterill, S. (2010). Pre-performance routines in sport: current understanding and future directions. International review of sport and exercise psychology, 3(2), 132-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2010.488269

44. Foster, D. J., Weigand, D. A., & Baines, D. (2006). The Effect of Removing Superstitious Behavior and Introducing a Pre-Performance Routine on Basketball Free-Throw Performance. Journal of applied sport psychology, 18(2), 167-171. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200500471343

45. Mesagno, C., Beckmann, J., Wergin, V. V., & Gröpel, P. (2019). Primed to perform: Comparing different pre-performance routine interventions to improve accuracy in closed, self-paced motor tasks. Psychology of sport and exercise, 43, 73-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.01.001

46. Lidor, R., & Mayan, Z. (2005). Can beginning learners benefit from preperformance routines when serving in volleyball? The Sport psychologist, 19(4), 343-363. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.19.4.343

47. McCann, P., Lavallee, D., & Lavallee, R. (2001). The effect of pre-shot routines on golf wedge shot performance. European journal of sport science, 1(5), 1-10 https://doi.org/10.1080/17461390100071503

48. Beauchamp, P. H., Halliwell, W. R., Fournier, J. F., & Koestner, R. (1996). Effects of cognitive-behavioral psychological skills training on the motivation, preparation, and putting performance of novice golfers. The Sport Psychologist, 10(2), 157-170. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.10.2.157

49. Hazell, J., Cotterill, S. T., & Hill, D. M. (2014). An exploration of pre-performance routines, self-efficacy, anxiety and performance in semi-professional soccer. European journal of sport science, 14(6), 603-610. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2014.888484

50. Mesagno, C., & Mullane-Grant, T. (2010). A Comparison of Different Pre-Performance Routines as Possible Choking Interventions. Journal of applied sport psychology, 22(3), 343-360. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2010.491780

51. Boutcher, S. H., & Crews, D. J. (1987). The effect of a preshot attentional routine on a well learned skill. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 18, 30-39

52. Rupprecht, A. G. O., Tran, U. S., & Gröpel, P. (2021). The effectiveness of pre-performance routines in sports: a meta-analysis. International review of sport and exercise psychology, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1(26). https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1944271

53. Didymus, F. F., & Fletcher, D. (2017). Effects of a cognitive-behavioral intervention on field hockey players’ appraisals of organizational stressors. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 30, 173-185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.03.005